About

My journey so far

Like basically everyone doing palaeontology in the UK, I was a big dinosaur kid, watching and reading anything a wee Scottish kid in a wee Scottish town could get his hands on about them. But, despite what you’re seeing here, I was also a quiet and shy kid at school… and rather afraid of sharks - something that probably stemmed from watching Jaws at far too young an age. Yet that passion for prehistory and that initial fear of sharks collided to form something new in 2003 when, aged just 6, I was first exposed to Otodus megalodon, the largest shark that’s ever existed.

This happened when watching BBC’s Sea Monsters, in which zoologist Nigel Marven time-travelled to prehistoric times to dive in the “seven deadliest seas” alongside some of the most iconic species known to have existed (in CGI form of course; not that that mattered to a 6 year old). One of these seas was from the Pliocene epoch 4 million years ago, where Nigel came face-to-face with megalodon. To wee Jack, it was mind-blowing that such an enormous shark had actually existed millions of years ago, swimming around eating whales. The following Monday at school, I was asking anybody who would listen if they’d seen “the giant shark” on telly. I’ve been hooked by the big fella ever since.

Although I had various career interests at school, and there are famously few jobs in palaeontology, I always came back to megalodon. Wanting to understand how something like that could possibly evolve, the natural subject to pursue at school and university was biology. This led me to pursue an undergraduate degree in Evolutionary Biology at the University of St. Andrews from 2014-2018. While St. Andrews did not have a palaeontology-specific degree, it did have the module “Biology of Dinosaurs and Other Extinct Vertebrates” where I attended seminars learning a range of topics in palaeobiology.

In 2017, during my degree, I learned of a unique opportunity to intern with cage dive operators in Gansbaai, South Africa - the great white shark capital of the world. Wanting to meet the most iconic shark species alive, I immediately applied. That summer, I was off to Gansbaai where two remarkable things happened. First, floating in a freezing cold cage, I finally saw a great white shark up close. And incredibly, there was no fear at all upon seeing it - just pure awe at the speed, size and power of this world-famous predator. But even more strikingly, three weeks into my internship, a white shark washed up dead on the beach with its liver missing - having been killed by a notorious pair of killer whales known as “Port” and “Starboard”. I got the unique chance to see the autopsy, and would write about the story of these two killer whales years later in The Guardian. In 2018, following my graduation from St Andrews, I returned to South Africa to take up yet another internship; this time in Mossel Bay. There, I saw white sharks almost every day, and gave my first public talk about the white shark and its conservation risks to a group of clients. Magically, a tourist captured a photo of a great white shark swimming right by me as I was chumming, one of my favourite pictures that you can see on the right. I only became more determined to make sharks my career; and decided to go back to my roots in palaeontology as part of that career.

My next destination from 2018 to 2019 was the University of Bristol to do a masters in Palaeobiology. I quickly became known as the “shark guy” amongst my peers. Then, three months into my degree, I had a full-circle moment. The masters project list was published by staff, and amongst them was a project titled: “External anatomy of megalodon” - to be supervised by Bristol’s Prof Mike Benton and externally by Dr Catalina Pimiento of Swansea University. I immediately, and very loudly, made my interest in the project known to Mike and sent an email to Catalina describing my recent background in shark work before students had even been assigned projects. Catalina was (and still is) the only person on Earth to have two postgraduate degrees on megalodon; clearly the world-leading expert. Having read her papers during my undergraduate, I was desperate to get her approval to join the project. Something must’ve worked as before I knew it, I was assigned the project. Using five living sharks with similar traits to megalodon, I quantified the relationships between individual body dimensions and total body length and applied them to megalodon - providing the first ever estimates of a megalodon’s head, dorsal fin and tail size amongst other measurements. I went on to achieve a distinction in my degree.

A PhD was the logical next step and as far as I was concerned, there was nobody else I wanted to work with other than Dr Catalina Pimiento, who was looking to start her lab group and find her first PhD student. In the following year, while looking for PhD funding and working in a Greggs, I joined her and her collaborator Prof John Hutchinson to start 3D modelling megalodon based on the most complete vertebral column in the world, which we would later use to make ground-breaking ecological conclusions. During this time, we acquired funding for a 4-year PhD studentship from the Fisheries Society of the British Isles; and successfully published my masters project on megalodon as my first scientific paper. The media response was immediate and intense; and within hours of the paper being published, I was on BBC News. Little did I know that this would be my first real step into science media and communication. Even better, Nigel Marven - the very man who’d dived with megalodon in the very show that had captivated me - tweeted about the paper; and I went on to meet him in person three years later in London (see photo!).

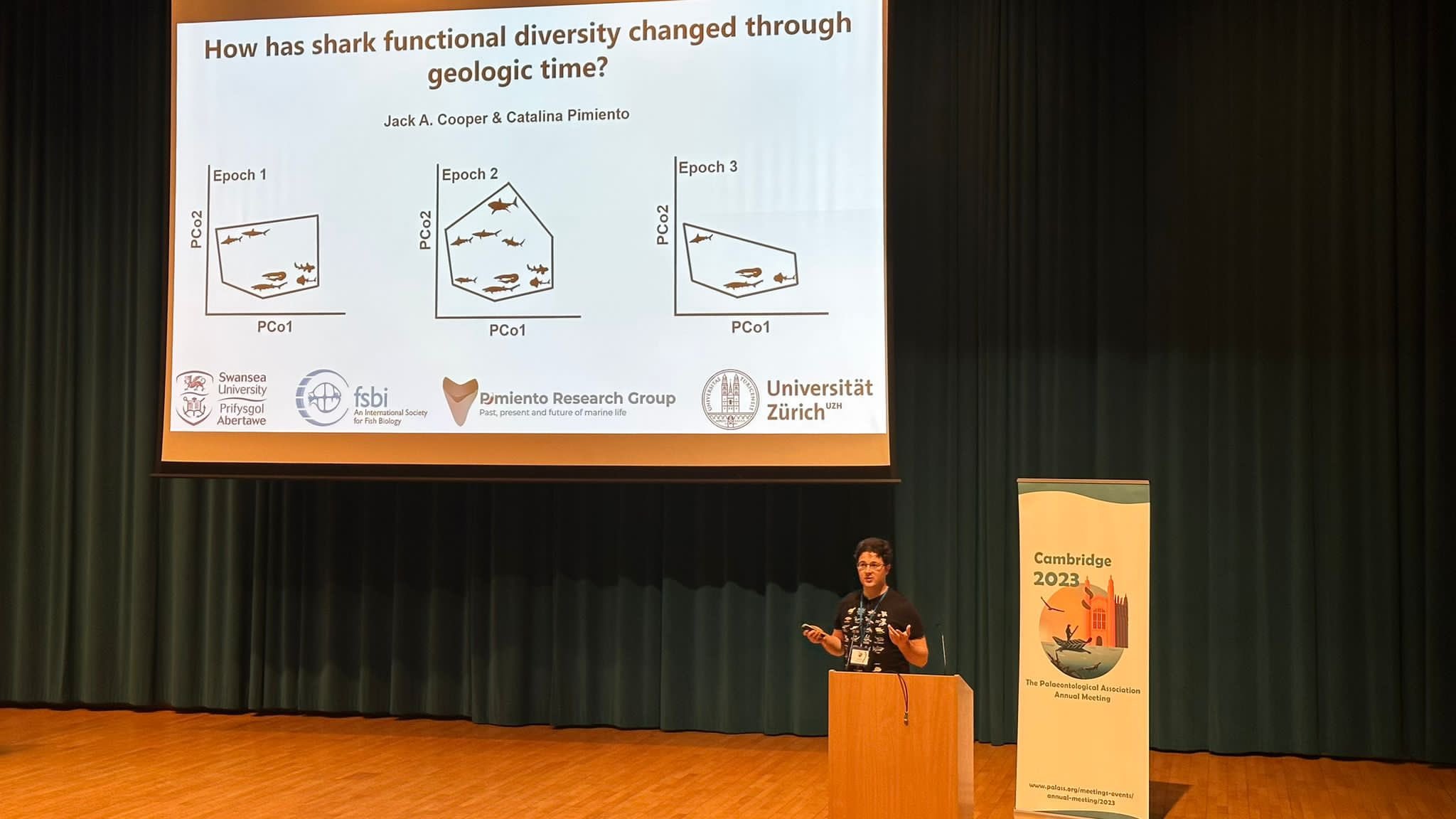

In September 2020, I moved to Swansea to begin my PhD in shark functional diversity through time; now suddenly known to the scientific community. In the 4 years I spent there, I got to be part of the newly formed Pimiento Research Group as it went from strength to strength; and I published four more papers; including the megalodon 3D model, leading to even more media attention, and two chapters of my PhD thesis. But even more significantly, the attention generated from my megalodon work led to a wide number of doors opening to me to be a part of science outreach. I went on my first podcasts, I worked on multiple documentaries, I was writing guest articles for the likes of Geoscientist and The Conversation. By the time I successfully passed my viva in September 2024, I was finding communicating my research as compelling narratives for broad audiences to be equally as rewarding as publishing a paper.

In the age of unprecedented misinformation circulating online about science, and increasing awareness of “fandom” style attitudes towards iconic animals and palaeontology rather than scientific discussions; it is now more important than ever that experienced scientists engage in good science communication. Sharks are a prime subject in need of this, with current research revealing that their populations have halved since 1970, and that over a third of all species are threatened with extinction, with overfishing as the overwhelming leading threat.

My goal as a science communicator is to generate public empathy for this iconic group of animals, which is crucial for supporting urgent conservation actions being proposed in the scientific literature. I aim to do this not only through public speaking about my research and others, but by collaborating with the arts: storytellers such as journalists, documentary filmmakers, and animators. My own writing also informs this goal. Media is at its most powerful when it is generating empathy, and thus I hope to be a small part of its turning point for these species, from the springboard of history’s most famous extinct shark. After all, if we can get people to care about a big scary extinct shark, then just maybe we can do the same for the sharks still with us today, and in need of our help.

Thanks for visiting my page! Feel free to browse around - you can read about my research topics, my writing portfolio, my various different media experiences, and my public speaking events. And if you want to hire me for any of this, then please get in touch and let’s make it happen! Fin.